Projects

Current Fieldwork/Research

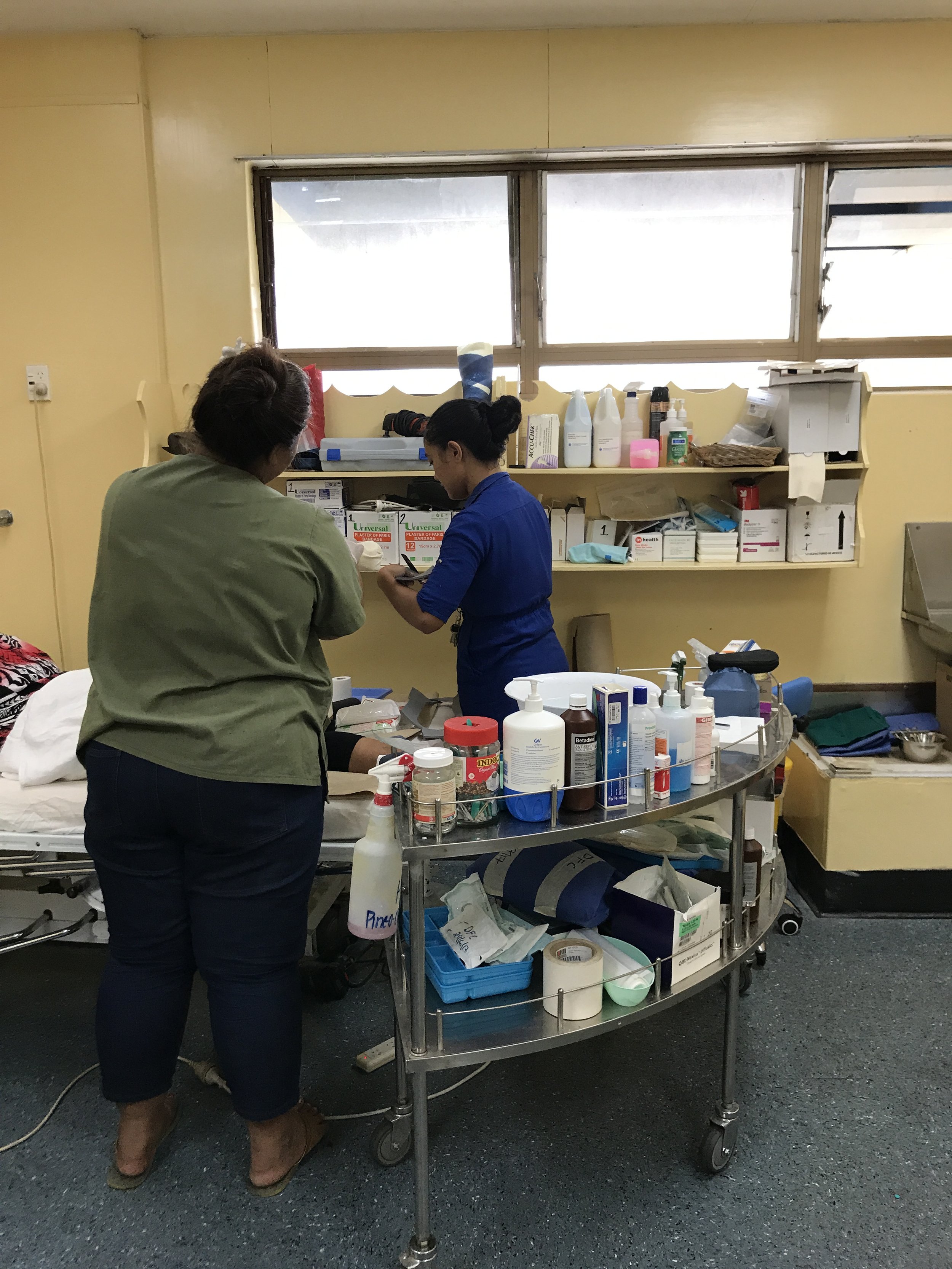

Trust and Medical Decision Making

This collaborative project brings together scholars and practitioners from across the Pacific —Vanuatu, Fiji, Samoa, Aotearoa, Australia — to study the role of trust in medical decision making. The team - John Taylor, Tarryn Phillips, America Ravuvu, Gate Waqa, Ramona Boodoosingh, Salome Wright - takes inspiration from our individual research findings - that patients are often blamed for not seeking healthcare in a timely fashion - to understand why. The project asks - what about healthcare systems that make them undesirable places to seek care? We will explore trust from the point of view of each field site, examining both distinctions and similarities across place, to understand how mis/trust influences the kinds of care that people seek. We’ve started to write about this work in the Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. This work is funded by the Australian Research Council.

Med Tech for Chronic Illness: Patients, Providers and Designers

This pilot project will explore the potential scope and scale of an ethnography of engineering and design, taking a feminist lens to explore how forms of social difference, like race, class and able-bodiedness, influence the design process in the area of access technology—that is, technologies designed to enhance accessibility for people living with varied abilities. It centers on the social practices involved in what is often referred to across disciplines as “the design process;” the project critically examines how users, clients and needs are socially constructed and the implications this may have on the design process itself.

The design process often involves these steps: defining a problem, imagining and planning, creating, testing and experimenting, revising and improving and, finally, sharing. These steps involve both individual contributions (in what we might consider as vision, intuition, and skill) and social dynamics (in what we might consider are values, including collaboration, iteration and team-work). Anthropologists understand both of these aspects as cultural processes that can be studied through an interactional and discourse-based lens, revealing how the design process unfolds in particular social contexts. This work explores “the design process” not as a singular, neutral mode for creating material culture and knowledge but as a social practice with discrete impacts in the world. It will pilot ethnographic methodologies including participant observation, informal interviewing and semi-structured interviews in classrooms, labs and studios to understand knowledge socialization (and innovate undergraduate education) and learn the jargon and conceptual toolkit that engineers and designers rely upon in their design processes (to develop collaborative relationships with medical technology developers). As a critical project, the potential social benefits of this project revolve around questions like these: What are the consequences and limitations of imagining complex and diverse humans as clients or users? What are alternative ways of imagining users or clients? The project can contribute to wider public discussions about equity and medical technologies.

Prevention’s Archive

When did prevention arrive as public health staff, colonial administrators and clinicians began to see diabetes and obesity arise in the Pacific Islands? How did prevention the prevention message - eat less, exercise more - become the only solution to rapid epidemiological change? This work tracks prevention as an idea and set of policy norms and public practices through the Pacific.

Histories of global health have largely focused on colonial medicine, agenda-setting in the context of development, the failure of communicable disease interventions and the emergence of the primary healthcare movement. This scholarship tends to also focus on regions like Africa and Latin America with little attention dedicated to the Pacific Islands and non-communicable diseases like diabetes. Histories of diabetes, which also neglect the region, have demonstrated how diabetes science racializes populations as out of sync with modernity. The absence of critical attention to the Pacific Islands is notable given the outsized role of the region in theorizing influential concepts like the epidemiological transition. By looking to archives of the South Pacific Commission, the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, I ask, how are Pacific islanders racialized through prevention discourses? How is research from the Pacific used to shape broader prevention efforts and theorizing about rapid change? How does prevention racialize?

This book project aims to understand the formative role that this confluence of development and colonialism in the Pacific Islands shaped broader global approaches to non-communicable disease. It makes the critical observation that after over 50 years of a prevention only approach, rates of diabetes continue to rise around the world. In the face of this failure, why does this approach continue to dominate global health paradigms and programming? What invisible role does the Pacific play in shaping some of these sensibilities? Why did this discourse approach to prevention flourish while a systems approach to healthcare dwindled? What is it about the logic of prevention that enables its staying-power despite its ineffectiveness? How did these policy makers, clinicians and public health experts come to see prevention as the only mechanism for making change? What might this moment reveal about the entrenched health disparities we live with today?

Current Writing

Complications: How Prevention Fails in the Pacific Islands and Beyond

This book investigates the global failure of prevention efforts to stem the tide of diabetes and related disorders in the Pacific Islands. To do this, the project tracks the emergence of prevention as a global health paradigm in the second half of the twentieth century, weaving together ethnography about the everyday experiences of prevention, diabetes, and diabetic complications like lower limb amputation in Samoa with a historical approach to the emergence of diabetes science in the Pacific islands. At the complex intersection of post-coloniality, development and global health, the book questions the emergence of a now globally hegemonic idea––namely, that to eat less and exercise more is to prevent diabetes. My interdisciplinary approach will broaden our knowledge of the history of diabetes by exploring the outsized role of research about the Pacific islands in informing broader global health paradigms.

The book develops a temporal theoretical approach to prevention by drawing out ‘as if’ and ‘as though’ frameworks for understanding the failures of prevention. The first half of the book focuses on how scientific approaches to understanding how societies around the world shifted from disease profiles of predominantly communicable diseases to non-communicable requires separating populations by variable. In the Pacific Islands, this has meant that scholars have adopted the paradigm of natural experiments (i.e. an epidemiological approach to using real life conditions that mimic the ideals conditions of a random control trial) and separated populations by gradients of exposure to “modernization.” I argue that holding still populations “as if” if they were purely “traditional” and then comparing these populations to populations “as if” they were “modern” is not only simplistic but also contributes to the racialization of populations through scientific paradigms. Even further, this kind of framing then becomes the predicated foundation for prevention that positions “traditional” populations as healthier because of their lack of exposure to the variable, modernity. In turn, prevention efforts become focused on returning populations to those traditional conditions, which were simplified in order to meet the needs of a experimental model.

The second half of the book explores how prevention is informed by an “as though” frame. The ethnography tells stories about how prevention messaging presumes that healthy foods are affordable, that people can grow their own healthy foods, and that health foods are desirable. These are all “as though” conditions created by the scientific modeling that underpins global health paradigms. The fictions that prevention sustains - that foods are affordable, life is relatively stress free and physical activity can be easily incorporated into one’s daily routine - certainly reflect individualistic, biomedical assumptions about health but they are also deeply rooted in the scientific infrastructure that undergirds evidence-based approaches to the global epidemic of diabetes. The second half of the book includes rich ethnography that demonstrates the fictions of these undergirding ideas.

Overall, the book demonstrates that what is often neglected in the global literature on diabetes is that to live with diabetes is to actually live with complications. It argues that by taking a temporal approach, we can see how prevention may actually be a driver of complications because of the ways that prevention occludes from view the realities of living with diabetes and the structural, and colonial, conditions that created environments where diabetes effects everyone. The book will make contributions in anthropology, Pacific Studies and in cross-over spaces in critical studies of global health. The fieldwork for this project was sponsored by the National Science Foundation, the Wenner Gren Foundation, and Fulbright.

Duo, Feminist Collaboration

Since 2019, I have been a member of the Nutrire CoLab, a group of women scholars who identify as feminist, anti-racist, and are mostly anthropologists. Nutrire is from the Latin, “to feed, to cherish.” In Spanish, nutriré means “I will nourish.” We originally came together to articulate a critique of the framing of metabolic illnesses as “diet-related” and to offer instead an understanding of these as a result of policies that are racist, patriarchal and rooted in settler colonialism. Our interests have expanded since to creating a space as feminist scholars to nourish each other: sharing resources, co-mentoring, and co-laboring to produce new bodies of scholarly work and public engagement. We produce a podcast, led by Megan Carney, that highlights some of our work.

One method we have used to create and sustain CoLab is duo-ethnography. We define this method as a feminist praxis, a method of mutual curiosity and interpretation. We have papers published in Field Methods and Feminist Anthropology based on this on-going work.

Past Research

Christianity and Health

My first book, Faith and the Pursuit of Health: Cardiometabolic Disorders in Samoa (Rutgers University Press 2019), offers a critical medical anthropology analysis of Pentecostal efforts to address rapid epidemiological change. During fourteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in Samoa, I participated and observed in clinics and churches while interviewing a range of health professionals. The book introduces the theoretical framework of embodied critique to examine how Pentecostal practice encouraged people to re-learn how to interpret bodily knowledge around fluctuations of glucose, stress or blood pressure in ways that used a salvational logic to materialize metabolism. In turn, the environment that fostered sicknesses like diabetes became the focus of critique, as the human origins of suffering came to the fore of their attention. This research was supported by the Wenner Gren Foundation and a Fulbright-Hays.

Fatness in Cross-Cultural Perspective

Working in a multi-disciplinary group, four anthropologist including myself and a biocultural anthropologist, an comic anthropologist and linguistic anthropologist joined together to understand how fatness was understood socially and culturally in our respective field sites - Georgia (US) (Sarah Trainer), Samoa, Japan (Cindi SturtzSreetharan) and Paraguay (Amber Wutich). We came together because these field sites are often used in the research on the global spread of obesity as a gradient with Samoa standing in for the most “fat positive” and Japan the most “fat negative.” Instead of aiming to measure these field sites against each other, we developed a collaborative and comparative ethnography focused on urban women’s experiences of fatness. What we found, which does not show up in the large scale studies of weight stigma, is that across the field sites there was a high degree of expressed fat stigma. Most importantly, in each field site people developed critical theories for this rapid change in body weights - namely stress, economic inequalities and social change. This project was supported by the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust through the Mayo Clinic/Arizona State University collaboration, Obesity Solutions. We wrote Fat in Four Cultures with undergraduates in mind and a paper about our methods in the International Journal of Social Research Methods.